31.12.1996

1996/97

The growth of global networking creates a need for new forms of political organisation and co operation. Is federalism really the political system of the future, and one which can enable the capabilities and flexibility of networks to bear fruit? Or does it generate new constrictions? The principle of subsidiarity has restored the notion of community and private autonomy to the centre of attention.

William H. Stewart (1) is an American political scientist who teaches at the University of Alabama. He has combined a meticulous scientific approach, the passion of a collector, and a refreshing sense of fun in assembling no less than 495 different definitions of federalism, arranging them in alphabetical order, accompanying them with textual extracts and quotations, and commenting on them in a witty introductory essay. In so doing, he has documented not only the huge variety of federalistic structures recorded in the history of ideas, institutions and events, but also the vivid imagination applied by academic and political commentators in their unceasing efforts to find or invent new adjectives and metaphors to express the complexity of the federal ideal. Morton Grodzin, for example, describes American federalism as „marble cake federalism“, that is to say a type of federalism „in which ingredients of different colours are combined in an inseparable mixture, whose colours intermingle in vertical and horizontal veins and random swirls“. Other similes from the culinary field include „spaghetti federalism“ („the image of spaghetti comes from simultaneous trends of diversity and convergence“, p. 161), and „sweet and sour federalism“, in which it is apparent that federal subsidies are sweet, but the conditions and obligations attached to them can also strike one as sour.

Semantic differences

Difficulties can also emerge from the semantic differences between one language and another, and from the application of the term in specific historical and national contexts. The expression has been used on innumerable occasions to cloak individual ambitions with an appealing title. Yet it has equally been used to denigrate political opponents. The concept of federalism can be examined as follows (2):

In European discussion the particularly topical and divisive concept of federalism gives rise to difficulties of comprehension and difficulties of translation because of historically divergent philosophical and linguistic associations. The terminology customarily used in Switzerland, therefore, has an important role to play. Between 1798 and 1848 a period of rich interest for the history of ideas in our country Particularists, Federalists and Unionists confronted each other in Switzerland. This epoch in Swiss history is of the highest relevance to the current process of European unification, although our experience should not be transferred directly to the European context. Yet even that long ago, Swiss people may have paid too high a price in terms of centralisation to achieve a much needed liberalisation…

Federalism also plays an important part in the history of the United States, although political conflict was characterised by discord between Federalists and the autonomistic (and, in later years, secessionist) anti federalists. No support existed for unionist plans, i.e. there was no significant political grouping campaigning for a central, unified American state.

Federalists in Switzerland thus were, and remain, anti centralist in attitude, in contrast to the unionists, and consequently support cantonal autonomy within the federation. The federalists, literally translated the „binders“, were, however, against the unlimited autonomy of member states within a loose national federation and were for strong, national, federal collaboration with major powers in the hands of the federation, and thus centralistic. There has been no fundamental metamorphosis in the concept of federalism, simply two significantly different original historical situations. An important distinction still applies today between the term „confederation“ and the term „federation“, in which the federalists prefer a federation to a confederation and accord highest importance to the central body. The Confederalists, on the other hand, favour the trend towards greater independence for member states.

After the Second World War, during discussion of the constitution for federal Germany, a debate was held on federalism which resembled in many ways the Swiss debate in the 19th century and may well have been influenced by it. As in Switzerland, it centred around three options, in which the federalist model provided the middle path. The relationships in the current debate on the European Union are quite different. The options under discussion are confederation and federation, whilst a central European state is fortunately not yet on the agenda. We would therefore be well advised to recall Anglo American usage and, like Margaret Thatcher and John Major, to conceive of the federal element as an intensification and not as a relativisation of the central, federal elements in Europe. Reference to „federal structures“ in Europe is no cause for satisfaction among those who seek the greatest measure of independence and the highest level of minority protection within the Community. The Federalists are the „binders“, the supporters of the Federal State, and the protagonists of centralising tendencies in a Europe faced with the choice between confederal and federal features. This use of language strikes us Swiss as odd but is does shed light on the history of ideas.

This article provoked a number of thoughtful comments, which are described briefly below. Compromise between centralising and de-centralising aspirations is actually inherent in the concept of federalism. The classic debate on the subject was in fact opened in the 1787 „Federalist Papers“ by Hamilton, Madison and Jay (3). Jörg Baumberger makes the following specific points in his commentary on them:

„We have no cause to suspect the authors of the American Constitution of having a secret, centralist agenda. They strove clearly and legitimately for a federalistic constitution in the conventional, theoretical sense of multiple dependencies and the division of sovereignty. The political circumstances of the time nevertheless compelled them to defend their constitution on one main flank: against the case for greater rights for the member states.

One of the principal objections of the anti federalists to the Constitution was the lack of a Bill of Rights, i.e. a law listing individual liberties which could also be enforced against the central state, a criticism which applies with equal force to, say, the Maastricht Treaty. (In the USA, the Bill of Rights was soon to follow.) The reason for its omission was the same in both instances: no one could imagine that a central state, created expressly for the protection of the citizen against the tendencies of member states towards tyranny and interventionism and endowed with a central monopoly of power, could in the longer term repeat those very failures of member states at a higher level. Perhaps history is subject not only to the law of the centripetal force of the central regime but also to the law of under estimation of this force at the moment when such a central regime is established.“

The following further point may be found in Baumberger’s commentary on the history of the concept in France: „The so called 1790 Federation Festivals in France were manifestly a celebration of the absorption of the hitherto disorganised troops of citizens‘ soldiery into the centralised National Guard. The Federation Movement was an enthusiastic turn towards the Centre. By contrast, the „Federalist“ movement which the Jacobins eventually so bloodily suppressed was an unequivocally de centralising movement. Since then, the concept of „federalism“ has always had a negative overtone in France. There, federalism does not denote the artful combination of two opposing principles into a durable synthesis of multiple, shared sovereignties, but instead detestable things like feudalism, undemocratic rule and, ultimately, secession.“

In his commentary on the key distinction in the European debate between federalism and confederalism, Dieter Chenaux Repond points out that:

„We in Switzerland could have progressed much further in our dispute with the European Union had we ourselves not repeatedly helped to confuse the concept. Confederalists support not merely „a high degree of autonomy on the part of confederation members“, but rather their total sovereignty within purely contractual limits. Federalists, on the other hand, support a substantial measure of autonomy within the framework of a single state and of a common destiny. In any case, whether confederalists with their unrelenting insistence upon autonomy, freedom, and minority protection adhere to their principles better than federalists is highly doubtful, especially if one takes Switzerland as the example. The Swiss Confederation recognised only one absolute principle: the liberty of the local authority. The protection of individual and minority rights is a task which only the federal state has assumed. From the perspective of history, Berne most definitely endowed us not with less but with more liberty.“

This last thesis can scarcely be refuted, but it can be contested.

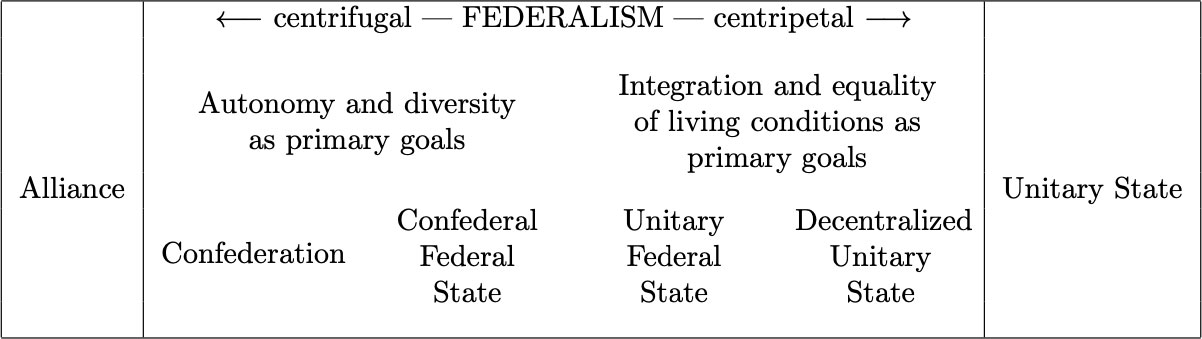

Perhaps the best way to escape the concept’s confusing history is by sticking to the literal translation. „Federalists“ are, in the original meaning of the term, „binders“, so that the Anglo-Saxons, who mainly detect the centralising tendecy, are not entrely wrong. The European Union, as currently perceived, is an institution which posseses the features of both a league of nations (confederation) and a federal state (federation). „Federalistic“ does not solely mean the opposite of centralistic but also designates an alternative to „autonomistic“, „particularistic“ or „confederalistic“. Consequently, in disputes amongst autonomists, particularists and confederalists, federalism is the expression of acentralizing tendency, whereas in disputes with centralists it expresses a de-centralizing tendency. Rainer Olaf Schultze provides a lucid illustration of this point in the „Dictionary of State and Politics“ (4).

A comprehensive study and tribute to the revolutionary dialectic between the unitary state and federalism in France can be found in the reprinted edition of Hedwig Hinze’s book on „The Indivisible Nation and Federalism in France“, first published in 1928 (5). The author convincingly demonstrates why and to what extent the French State regarded itself as the promoter of centralisation, and how in that country nationality, nationhood, justice, order and centrality became so blended into an overriding principle that even de centralisation could only be perceived as a process performed by the centre. The book also provides between the lines a valuable insight into the French perception of the European Union.

In the USA after the Second World War, growing emphasis was placed upon the liberty enhancing aspects of „federalism“, since elevated by the increasing popularity of conservative values to a fundamental principle of political morality. Felix Morley thus writes in his 1959 book „Freedom and Federalism“ (6) : „that liberty under God is man’s most precious birthright, and that our best means of securing Liberty is through the political device of Federalism.“ A liberal (in the European sense) plea for federalism with a decentralist tendency may be found in the very rewarding writings of Clint Bolick (7).

„Federalism“ in the former Eastern Bloc

In the international discussion of the concepts „federalism“ and „regionalism“ after 1989, confusion has had plenty of time to spread and flourish. Within the former Soviet Union, the term „federalism“ was customarily employed to emphasise centripetal forces. Exhortations for a „federative spirit“ were synonymous with exhortations for solidarity amongst „brother nations“. The objective was quite plain: „federalism“ meant endowing central government in Moscow with additional powers, and thus the reinforcement of common bonds and universal duties. According to this definition of the term, a „federalist“ was, and remains, a supporter of centralist tendencies. Even within the „Commonwealth of Independent States“ (CIS), where Russian thinking on power and ideology remains deeply entrenched, the term continues to carry this centralising connotation. There it signifies an emphasis on the binding, communal element, as opposed to total, national independence and the autonomy of member states. Whether one judges this use of the word as a terminological inexactitude, or observes that, in common usage, a long established trend in the evolution of words and ideas has simply moved further in one specific direction, makes little difference. What really matters is that one should be fully aware of the fundamental difference between Central European and Eastern European usage on the one hand and the historically rooted perception of „federalism“ encountered particularly in Germany and Switzerland on the other. A participant in a heated debate who points out that the disputed „differences“ might possibly be semantic in nature, and might not arise from philosophical or political disagreements will often be labelled as a hair splitter, a pedant, or even as an obstructionist. This should not deter us from taking a closer look at the problem.

Regionalisation and transformation

The idea suggested by the principle of subsidiarity of having multiple levels of authority, in which the burden of proof lies with the proponents of centralisation, and in which expression is given to the endeavour of implementing autonomy in as decentralised or non centralised way as possible, is often referred to in Central and Eastern Europe by the term „regionalism“. In so doing, it is often overlooked that there is an important difference between the gradual construction from the bottom up of a confederation or federation from formerly autonomous entities and the systematic decentralisation from the top down of a system formerly administered both politically and economically from the centre. Both processes may be referred to as „regionalisation“. The transformation is beset by almost insuperable difficulties, especially if one attempts to maintain the pretence that one can combine the advantages of both procedures. In practice, one is more likely to combine the drawbacks of both…

When actual transformations proceed, there is in fact a third scenario: the uncontrolled collapse of central governmental structures combined with the creation or revival of small local, neighbourhood, and family based structures. These involve the formation of spontaneous community movements at the level of small and very small entities. Typical examples include those schools in which parents associations support the „educational institution“ in improvised ways by continuing to meet at least part of the schoolteachers‘ wages when central government no longer foots the bill. The term „regionalisation“ is not applied to this form of self administration because it involves the emergence of unplanned, preponderantly horizontal agreements and mutual exchanges. In this area, the principle of subsidiarity operates in its original sense, as a division between spontaneous or organised private structures on the one hand and public institutions founded upon statutory authority and fiscal resources on the other. The concept of de centralisation is equally inappropriate in this context because there is no competent central authority consciously delegating its powers to subordinate bodies, only the more or less obvious chaos of the collapse of authority and the takeover by partly corrupt, partly creative private initiatives, by black markets, grey markets and legitimate markets. Terminological misconstructions thrive during such a process. Are we seeing true examples of „regionalisation“ or „federalisation“, or merely manifestations of private autonomy?

Cross border and boundaried regionalism

In Switzerland, the principle of „regionalism“ co exists with the notion that certain public functions need to be performed not within the limits of traditional community boundaries, but at a cross border level: inter communally, inter cantonally, or even in the case of regions with international frontiers trans nationally. Here, the region is regarded as the alternative to a small scale local solution. The idea of cross border collaboration is then the guiding principle. The situation is perceived differently in regions which are sub divisions of larger national states, and which for historical or ethnic reasons aspire to greater autonomy, such as the Scottish in the UK, the Bavarians in Germany, and the Northern Italians in Italy. In these places regionalism represents the alternative to the centralist tendencies of the national state. A similar variety of regionalism is to be found amongst the bankrupt regimes which were the centrally administered satellites of the now defunct Soviet Empire. Here too, regionalism does not mean „cross border links“ or „co operation“, but rather the creation of new frontiers. In this context there are two political trends: that of the reformers, who believe in a gradual re building and re organisation of the old, centralist structures, and that of the radical innovators, who see a solution only in the outright rejection of an insolvent, dysfunctional, and parasitical central bureaucracy. Technocratic feasibility mania on the one hand, — faith in the creative power of spontaneous transformation on the other. The main problem in this situation is, in fact, the peaceful completion of vitally necessary partial secessions, whose purpose is the achievement of new autonomy through the creation of new boundaries with both superior and neighbouring powers, yet without inciting the taxation, police, or military forces of the former superior or neighbouring power to aggressive intervention. The term „secession“ has disagreeable associations for us. But how else are we to describe a process in which the principle of subsidiarity rebuilds from the bottom up, in which it initially questions and ignores everything central.

Centralism versus Protectionism?

In a monograph entitled „The Options for Federalism“ (8) which is generally supportive of the principle, the German political scientist Fritz Scharpf speaks of a „zero sum power conflict“. Considering the existing shortages of funds at all levels and the limited scope for tapping new sources of fiscal revenue, this is a realistic assessment. According to Scharpf, federalism in Germany has no future without constitutional reform of a kind whose „objective would be to restore to the Laender the authority to enact laws, raise taxes, and implement structural plans , that is to say to each Land individually.“ He rightly regrets that this insight has not yet been widely recognised, since his thoughts do not coincide with the dominant trend within Germany towards centralisation. They therefore deserve one’s attention, as do his warnings about European economic policy which „restrains the protectionist tendencies of national states and replaces it with the growing protectionism of the Community“ (p. 12). The flexible „niche“ strategy which Scharpf attributes to Switzerland (he mentions tourism, financial services, and boarding schools) was more the initiative of private enterprise than of a narrow national or member nation economic policy. The same accusation of protectionism could be made here at the domestic level as Scharpf expresses against the EU. In the course of history, centralisation has repeatedly been promoted by liberals and free trade supporters as the antidote to member state protectionism and interventionism, as a contributory factor in generating commercial opportunities through privatisation and de regulation. This is why liberals in Switzerland, like the free trade „federalists“ in the USA before them, favoured greater federal powers. In view of the dubious track record of the formula „de regulation under the supervision of central authority“. one must ask oneself whether such a strategy has not proved to be a dead end, and whether free competition amongst sub-systems for the best possible solution would not be at the end of the day have resulted in (would not in the future result in) more autonomy for all…(one states this at the present juncture merely as a counter argument to Chenaux Repond’s comment about the liberty enhancing power of centralisation.)

Federalism and local autonomy

It is also striking that, in the Swiss debate on federalism, only the relationship between the Confederation and the Cantons is usually discussed, and that the theme of “ autonomy at a local level“ is dealt with under a different heading. There are reasons for this (9). The Cantons, which for their part make a great deal of fuss (verbally, at least) about their rights vis à vis the Confederation, and adopt an anti centralist posture (as long as it costs them nothing), nevertheless conduct themselves in a centralist manner vis à vis the local authorities (except where the decentralisation of costs or other political problems are concerned). The only counterweights to Cantonal centralism are the numerous local authority representatives who, as a rule, account for at least one third of the members of Cantonal parliaments. But the support for independence given by this „autonomy lobby“ is also motivated in the main by fiscal considerations and the desire to increase personal political power, i.e. people want more authority but without paying any more for it. In a subtle in Switzerland generally under appreciated study of communal autonomy in Graubünden, the American political scientist Benjamin Barber (10) reveals how „federalism“, i.e. the integration of Canton Graubünden into the Federal State, accelerated the death of communal liberty within the Canton instead of preventing it. This finding should be of interest principally to those who make an analogy between the establishment of the confederal state in Switzerland and the process of integration in Europe, and who dream that an increase in Cantonal, regional and local autonomy will result from entry into the EU, because „Brussels“ is farther away than „Berne“. The notion that federation at a higher level would inhibit the powers of subordinate federations whilst enhancing those of communal, regional and cantonal authorities could well prove a fatal illusion. Historical precedent invariably shows that the cession of sovereignty at whatever level is a one-way street. It is perhaps no coincidence that it should take an American and an outsider to diagnose the death of liberty at a communal level, whilst these same communal units continue to be celebrated in our textbooks on citizenship as the „germ cells“ of our nation. Admittedly, Switzerland’s communities are in no sense dead. However, their autonomy is in poor health and the potency of these germ cells is as unimpressive as that of the cantons. In my view anyone who is serious about the „spirit of federalism“ and the associated principle of subsidiarity should definitely put the autonomy of local authorities on his agenda. The local level is where transparency between services and spending could be most readily achieved and where power can be monitored, not just institutionally but personally. Communities could also experiment with reforms like privatisation plans and voucher systems. They could then become pioneers of innovation instead of its narrow minded inhibitors.

Lessons from the past

The debate about federalism began in Switzerland at the start of the 19th century (and not, as Riklin states, quoting de Rougemont, in the first volume of the „Handbook of the Swiss Political System“, „…towards the end of the 19th century“) (11). Jürg Stüssi Lauterburg’s study, with its extensive collection of source material, definitely has the right title; it deals with the revolt in 1802 against the Helvetic republic which had been centralised by the French invaders and is called „Federalism and Freedom“(12). In view of the forthcoming 1998 Constitution Jubilee Celebrations, the book deserves the special attention of those who set great store by the „200th Anniversary“ of the demise of the „Old League“ and who like to regard Napoleon as the freedom loving restorer of federal structures. The book begins with a fanfare of a sentence which encapsulates the central arguments:

„The 1802 uprising forced Switzerland to adopt federalism, led Bonaparte to intervene once more in our country, contributed to England’s declaration of war against France in the year 1803, and moved Schiller to write about William Tell.“ The complex events of that era are often considered only briefly in schoolbooks and from the viewpoint of local patriotism, and certainly not as the book’s sub title rather grandiosely but not unjustifiably states as „A Chapter of World History written in Switzerland“. Napoleon saw „les fédéralistes“ as enemies, and he contrasted them with „les patriotes“, the friends of France. Footnote 35 on page 344 reproduces Napoleon’s original words: „il faut que, pour ce qui regarde la France, la Suisse soit francaise, comme tout les pays qui confinent à la France“. [„it is essential, in France’s national interest, that Switzerland should be French, like all the countries which have borders with France“]. As regards the country in which the true friends of an independent Switzerland then resided, this too can be gleaned from the same historical sources: „In 1803, England took up arms against France for reasons which included Bonaparte’s occupation of Switzerland“ (p. 281).

Fresh impulses

The principle of federalism acquired a fresh impulse from the challenge of a multiplicity of already existing overlaps amongst ethnic groups, politico historical frontiers, and commercial links of both a structural and infrastructural nature. The reality of multi-cultural societies in which there is a sharply defined division of labour, is patterned more like a leopard-skin than chessboard. In any number of respects, the model of „strict separation of territorial and fiscal powers“ has today become obsolete. In the last resort, it leads to the madness of „ethnic cleansing“ notoriously exemplified by Bosnia. The two economists Reiner Eichenberger and Bruno Frey recently published a brief outline of a model for „dynamic federalism“ in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung ( „Eine fünfte Freiheit für Europa“, „A Fifth Freedom for Europe“, NZZ, No. 30, 6th February 1996) (13). In many respects the model is topical since it involves overlapping, competing statutory communities. The „FOCI“ (Functional Overlapping Competing Jurisdictions), each one referred to as a „FOCUS“, are constituted „in accordance with the function to be performed“, and since every function requires a further extension of their jurisdiction, they compete for communities and citizens by what they are able to offer. They have the power to raise taxes and herein lies both their key advantage and the greatest obstacle to their realisation. Perhaps one should, right from the outset, talk not about taxes but about prices, charges, or indeed „membership fees“. After all, what existing district corporation with an empty treasury is going to relinquish its power to raise taxes, and what tax payer is actually prepared to accept new additional tax gatherers? The taxation screw probably cannot be tightened any further without producing drops in productivity and falling revenue due to the ensuing tax revolt. Yet it is possible that the so called bottlenecks in public finance will soon be recognised as dead ends. When the revolution happens, people will one hopes remember the „Zurich Focus Model“ which is not based on centralisation and harmonisation but instead promotes diversity, and without sacrificing too much flexibility. It might also avoid the „entanglement trap“, so clearly described by Scharpf, in which consensus and compromise evaporate and the willingness and ability to pay decline while public expectations, demands and requirements grow. In situations like this the moment comes in which private autonomy is rediscovered, since it represents a strategy for solving problems between the „haves“ and the „have nots“, a strategy based on the direct negotiation of compromises and the resolution of financial problems inter pares and as a rule inter vivos (that is to say, not at the expense of future generations). The credit limits of such contracting parties are linked to personal means or individual creditworthiness, and the price performance ratio remains continuously subject to the Damoclean sword of bankruptcy. Civil law functions through flexible and not generally enforceable contracts and thereby allows „Liabilities as requested and as required“, i.e. a minimum of compulsion and a maximum of efficiency. Whether the systematic extrapolation of the Zurich Focus initiative will eventually lead to a co operative model of self administration or to other private corporations and institutions is a moot point. What, after all, are service organisations (with or without public shareholdings and obligations) if they are not legally self constituted, functional, overlapping, competitive agents in other words: FOCI?!

The errors of regionalism

In his key study, „The Swiss federalism debate since 1960″(14), Georg Kreis has chronicled and meticulously recorded this development. The debate is characterised „by a disproportionate relationship between the analysis and the conclusions“ (according to Max Frenkel), and it is striking how great the discrepancy is between the high status accorded to politico ideological rhetoric and the low value placed upon serious research. The „Institute of Federal Co operation“, founded in 1967, has endeavoured to offer help in this area and has promoted, amongst other ideas, the principle of „co operative federalism“ and the concept of multi purpose regional associations. In all of this, however, the question of whether the regions are to be regarded as operating as a fourth level between the communities and the cantons, or as inter cantonal, or as trans national bodies, and whether they are alternatives or additions to existing area bodies, or even to be incorporated as private organisations, is left unresolved.

It is amazing how quickly the environmental planning debate in Switzerland about regionalisation and about the regional economic development of specific areas through subsidies and special loans has vanished from the top of the political agenda. As far as inter-regional financial equilibration is concerned, this is no cause for regret, since the idea is unworkable in the medium term and counter-productive in the long term. Money rarely achieves the promised and expected „fixes“ and may well be re directed into the wrong channels (i.e. back to central control), so that it may well be appropriate to speak of misdirected „development aid“ in the national context. The idea of magnanimously re distributing public funds within and among cantons has actually created more frustration than satisfaction and really amounts to nothing more than meddling, intervention by means of more and different compulsory harmonisations; a re botch of an existing botch. The concept of financial equilibration and of „aid“ to financially and structurally disadvantaged regions enjoys high political popularity like all compensatory projects in which one robs the rich to pay the poor. Just what proportion of such funds seep away during the process of re-distribution or are misdirected towards third parties unafflicted by hardship remains a secret known only to those very re distributors whose raison d’être and indispensability is justified by their re-distributive function. The enthusiasm for monitoring effectiveness within such constitutionally anchored relics from the era of happy go lucky interventionism is unsurprisingly low in government circles and amongst researchers, who are themselves partly funded by government.

There is, however, another aspect of the regionalism debate which, as Martin Lendi (15) rightly points out, remains to be addressed. The establishment and dismantling of infrastructure networks lead to a host of consequences which ought not to be dealt with exclusively by means of subsequent corrective measures. The ways in which people are involved and affected differ widely in regional, financial and individual terms; there is a legitimate need for preventive action both to minimise the unavoidable follow up costs and interventions and to break the vicious circle of publicly induced practical constraints and „financing traps“. This kind of communication is relevant to federalism inasmuch as it tries to bridge conflict with understanding and to make compromise possible. At its core lies the principle of openness, i.e. the making public of projects with all their processes and foreseeable financial, ecological and socio cultural consequences, as a precept of the democratic and constitutional state. For this very reason it cannot be the task of the regions, which have little or no political organisation, to lead the public debate on regionalism or to facilitate, enforce, or be accountable for the resulting decisions. The competent bodies for this task are the traditional, democratically accountable authorities: i.e. nations, federal states, and local authorities.

In the course of the 1990s, interest has shifted away from the interface between the Cantons and the Confederation. Today the most important problem facing domestic and foreign policy is Switzerland’s relationship with the European Union and thus the question of European federalism. The crucial question for Switzerland whether Europe in the 21st century will be a federation of subordinate states or a confederation of separate nations remains unanswered, as does the question of which compromise holds out the best possible solution.

References:

1 William H. Stewart: Concepts of Liberalism. University Press of America, Lenham (MD) 1984

2 Nef Robert: Liberal, föderalistisch konservativ. Vertauschte Mäntel beim Übersetzen (Liberal, federalistic conservative: Borrowed Garments in Translation) Schweizer Monatshefte, 74, 1994, S. 5 ff.)

3 The Federalists (Federalist Papers) (Hamilton, Jay, Madison), ed. H.C. Lodge, New York, London 1886

4 Schulze Rainer Olaf: Föderalismus, in: Wörterbuch für Staat und Politik, Hrsg. Dieter Nohlen, München 1991, S. 139 ff.

5. Hinze Hedwig: Staatseinheit und Föderalismus im alten Frankreich und in der Revolution, Frankfurt am Main 1989

6 Morely Felix: Freedom and Federalism, New York, London 1959

7 Bolick Clint: European Federalism: Lessons from America,

Institute for Economic Affairs. Occasional Paper 93, London 1995

8 Scharpf Fritz W.: Optionen des Föderalismus in Europa. Campus, Frankfurt am Main 1994

9 Linder Wolf: The Swiss Democracy, The Macmillan Press Ltd., Houndsmill 1994

10 Barber Benjamin: The Death of Communal Liberty. Princeton University Press, New Jersey, 1974

11 Riklin Alois: Handbuch Politisches System der Schweiz, Bd. 1, S. 57

12 Stüssi Lauterburg Jürg: Föderalismus und Freiheit. Effingerhof AG, Brugg, 1994

13 Frey Bruno/ Eichenberger Rainer: Eine fünfte Freiheit in Europa, in: Neue Zürcher Zeitung Nr. 30, vom 6. Feb. 1996

14 Kreis Georg: Die schweizerische Föderalismusdebatte seit 1980. In: Thomas Fröschl: Föderalismusmodelle und Universitätslehre. International relations in the early modern period from the 15th to the 18th century. Vienna Contributions to Modern History, Vol. 21, Vienna 1994. Italian translation in: Federalismo in camino, ed. Antonia Gili and Remigio Ratti, Lugano 1995

15 Lendi Martin: Schweizer Föderalismus und europäischer Regionalismus. In: Nach 701 Jahren – muss man die Schweiz neu erfinden? (Do we have to re invent Switzerland after 701 years?), Zurich 1992, p. 172